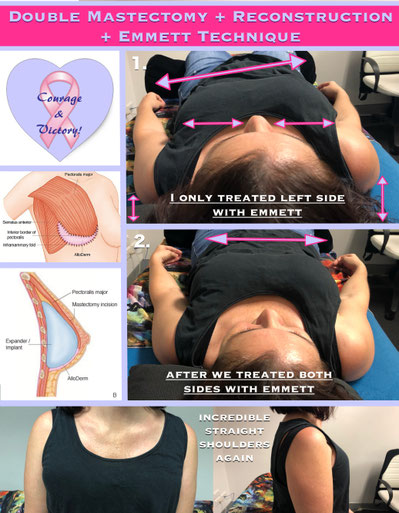

This is not an Emmett Article written below, BUT!! so many things written here can be related to what we look at when you first walk into one of our Emmett Technique clinic rooms. We actually

size you up :) we check out the way you stand, where your feet are placed, where your hips are sitting, where your head tilts, where your shoulders are at, what side you are bunched up on, how

you flow when you move.

Then and there we decide on a calculated group of moves based on what your body is showing us. Our aim being re-setting the muscle/movement memory back to its original balanced state. (The

article below talks about this)

Emmett is fun and quite an inspiring treatment to give and receive, as you get to see and feel the body change before your eyes. You will never receive the same treatment twice from one of our

therapists, and you will love the instant, long term pain relief results.

I Enjoyed Reading This Article about the Psoas Muscle So Much I Copied and Pasted It. The website I found it is listed at the end.

The Psoas Muscles, Groin and Back Pain -- Health and Symptoms and About Stretches and Exercises

This article gives a fairly comprehensive understanding of the condition. Health care professionals appreciate a technical understanding, so I'm laying it all out, here. However, if you are a

sufferer and not a health professional, you may want just a summary of the essentials on this page. Click Psoas Muscle Pain: 9 Central Questions and Answers, to get the summary.

SYMPTOMS AND LOCATIONS OF PSOAS MUSCLE PAIN ("ILIOPSOAS SYNDROME") Psoas muscle pain may show up as groin pain (psoas tendinitis or psoas bursitis), deep pelvic pain (lumbopelvic pain), pain deep

in the belly, or lower back ache (not sharp pain) at waist-level. The lower back ache doesn't come directly from the psoas muscles, but from the lower back muscles. Tight psoas muscles also cause

pain in the front of the hip joint and are the underlying cause of labrum tears of the hip joint and loss of hip joint cartilage (leading to hip joint replacement surgery). ("Labrum" means, "lip"

-- the lip that surrounds the joint surface at the hip joint.)

The iliopsoas muscles consist of the iliacus muscles, which span from each groin to the sides of the pelvic cavity; the psoas muscles span from the inner groin to the spine behind the breathing

diaphragm; because they share the same tendon at the groin, they are called, "the iliopsoas muscles". The iliopsoas muscles are large and long; pain may show up anywhere along their length.

THE ILIOPSOAS MUSCLES and QUADRATUS LUMBORUM

Tight psoas muscles put undue pressure on the bursa at the groin, causing iliopsoas bursitis and iliopsoas tendinitis. (A bursa is a fluid-filled sac that acts as a soft pully for a tendon that

passes across it.) Tight psoas muscles are in a constant state of fatigue and feel sore, giving rise to pelvic and abdominal pain. Iliopsoas syndrome is a collection of symptoms caused by tight

iliopsoas muscles and experienced anywhere along their length.

When is a Diagnosis of 'Tight Psoas Muscles' Wrong or Misleading? Sometimes, tight psoas muscles are only part of the problem -- or not the underlying cause (despite the diagnoses of well-meaning

practitioners and therapists). A twisted sacrum (sacro-iliac joint dysfunction), for example, produces psoas muscle symptoms; not knowing this fact, people may directly treat the psoas muscles

and fail to get relief -- or lasting relief, or complete relief. If you have symptoms in addition to those I describe, next, you may have sacro-iliac joint dysfunction. Here are some symptoms of

sacro-iliac joint dysfunction.

If you have some of them,

pain across your low back at the waist

pain along the border of your pelvis

deep hip joint pain a feeling like a tight wire at your low back

popping at your low back

a combination of low back and groin pain

THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM The root the problem is muscle/movement memory. Muscle/movement memory controls and shapes posture and movement. The intense sensations of injury (cringe response/trauma

reflex) and repetitive use patterns change muscle/movement memory in unhealthy ways. For example, an injury to leg or foot causes us to lift up the leg or foot and to hobble in walking; lifting

the leg and hobbling involve the psoas muscles. Repetitive use, as in sitting for long periods perched on the edge of a chair, tensely erect at a high level of concentration, causes a tension

habit to form in the muscles of sitting, which include the psoas muscles. Both situations cause muscle/movement memory to change. When muscle/movement memory changes, we end up in a new, habitual

state of tension. That tension causes muscle fatigue and pain. Muscle/movement memory can't be changed by stretching; muscle/movement memory is what we involuntarily return to after we stretch.

Indirect therapies use stretching, manipulation, massage, breathing and passive relaxation, visualization and/or skeletal adjustments. What they all have in common: none change muscle/movement

memory, but only seek to counteract the effects of muscle/movement memory. How do we know? Look at the results of such indirect approaches. Results are telling. Now, you may understand, why. The

more direct approach to eliminating psoas muscle pain changes muscle/movement memory at the self-control level, the brain level -- the approach explained, recommended and offered here.

ABDOMINAL STRENGTHENING EXERCISES AND PSOAS STRETCHES

People with psoas muscle pain often have a bulging belly. People may think that a bulging belly indicates weak abdominal muscles, but look deeper. A bulging belly often means too muscle muscle

tone (though too much fat and/or bloating are other causes). Muscles with too much tone develop the burn of muscle fatigue and pain, change posture, and restrict movement. Tight psoas muscles,

whose tendons pass over the inside of the groin and attach at the inner thigh, push the pubic bone back; the upper pelvis tilts forward; the belly hangs forward and appears to bulge.

The way people commonly think about these two conditions -- bulging belly and tight psoas muscles -- gives rise to the way people treat psoas muscle pain. Bulging belly: abdominal strengthening

exercises

Tight psoas muscles: stretching exercises You can't correct a bulging belly or tight muscles by strengthening or stretching. Here's why: Neither abdominal strengthening nor psoas stretching

exercises efficiently changes muscle/movement memory; muscle/movement memory determines muscle tone and the shape to which you return after you have stretched -- whether in hours or in days. You

keep returning to that tension, posture and shape. To get a lasting change, you need to change muscle-movement memory. There exists a way to do that.

When is Stretching Your Psoas Muscles, Wrong? The answer is, "Always." The most common approaches to psoas muscle pain involve stretching, massage and/or other attempts to get the psoas muscles

to relax. They don't work. The problem isn't that psoas muscles need stretching, but that they have too much muscle tone. Too much tone means wrong muscle/movement memory. Muscles with wrong

muscle/movement memory keep shortening and keep needing stretching. Even if you could get the psoas muscles to relax by stretching, stretching doesn't retrain muscles into healthy coordination

and healthy tone. For healthy tone, you need all the muscles of your movement system to be well-coordinated because they all work together in balance and movement.

So, the answer to, "When is stretching your psoas muscles, wrong?" is, "Always." Several reasons exist for the incomplete or temporary results of psoas stretches. "Muscle/movement-memory" runs

the show. Stretching creates only the memory of being stretched, and does not develop the muscle/movement memory that controls normal movement, muscle tone and coordination. In stretches, tight

muscles remain passive, while other muscles force the stretch. That makes stretching an indirect approach. The direct approach is to retrain muscle/movement memory by movement training that

actively uses your psoas muscles, normalizes their tone and improves your coordination. To normalize psoas muscle functioning, you need to cultivate direct control of the psoas muscles.

The most common psoas muscle stretch (the psoas "lunge") is done standing or kneeling. When you are upright, balance reflexes based on your old muscle/movement memory come into play, which

interferes with efforts to form new muscle/movement memory. In stretching, the tension of other, surface muscles (such as the gluteus minimus hip joint flexors) interfere. Stretches never reach

the psoas muscles.

To free your psoas muscles, you must gain control of the natural movements they cause. As you gain control, pain fades out and free movement returns. Direct control develops as you practice

movements in positions that directly involve your psoas muscles. With practice, you learn control by feel. "Control" means that you can do what you intend to do and not do what you don't intend

to do. Unless you mean to do a movement that involves your psoas muscles, they stay relaxed by themselves.

SELF-RELIEF PROGRAM PREVIEW TIGHT HAMSTRINGS Tight psoas muscles require hamstring muscles to overtighten to overcome the forward pull of tight psoas muscles. It works the other way, too: Tight

hamstrings REQUIRE psoas muscles to tighten up. If your hamstrings are tight, please read this entry and see the hamstring somatic exercise video, there.

Retraining muscle-movement memory is more effective (faster and durable) than stretching. The "lunge" shown, above, typically causes the back to arch. Tightening the abdominal muscles doesn't

adequately help to prevent the back from arching, and, in any case, sets up an unhealthy tension pattern in those muscles. The real issue, in any case, is muscle/movement memory -- tone and

coordination -- not the degree of stretch. If you don't change muscle/movement memory, nothing really changes.

Correcting the Bulging Belly A bulging belly may (and often does) indicate tight psoas muscles, not weak abdominal muscles, particularly if you have a deep fold at your groin that doesn't

disappear when you stand tall. When the psoas muscles function properly, they decrease the low-back curve and allow the spine and abdomen to fall back. The bulging belly settles back in, giving

the appearance of strong abdominal muscles and the feel of a strong (i.e., effortlessly supportive) core. But it's not strength that's being felt, but the feeling of a different trunk shape.

Preview a Guaranteed Self-Relief Movement/Memory Training Program.

The Relationship of Psoas, Abdominal Muscles and Back Pain The psoas muscles and the abdominal muscles are opposing pairs (agonist and antagonist) as well as synergists (mutual helpers). Closely

coordinated interaction between the two is healthy; poor coordination between the two creates problems. The psoas muscles lie behind the abdominal contents, from the level of your diaphragm to

your inner thighs at the groin (lesser trochanters); the abdominal muscles lie in front of the abdominal contents, from the lower borders of the ribs (with the rectus muscles as high as the

nipples) to the pubic bone.

Here's how they interact. AS ANTAGONISTS (opposition between muscles): When standing, contracted iliopsoas muscles (whose tendons ride over the pubic crests) push the pubic bone backward; the

abdominal muscles pull the pubic bone forward. Co-contraction creates abdominal compression and disturbed function of the internal organs. The psoas minor muscles pull the lumbar spine forward;

the abdominal muscles push the lumbar spine back (via pressure on abdominal contents and change of pelvic tilt). Deep Pelvic/Ilio-sacral (S-I) Joint Pain If you have deep pelvic pain, pain across

the lower back, burning bladder or groin (and no infection), or numbness down your thigh, please also read this entry.

AS SYNERGISTS (cooperation among muscles): In walking, the iliopsoas muscles of one side move the leg forward, and the abdominals bring the same-side hip and pubis forward. (discussed on more

detail, below) The iliacus muscles, which feed into the quadratus lumborum muscles, which feed into the intercostal (rib) muscles. All these muscles move the trunk in the twisting/untwisting

movements of walking. The psoas major muscles pull the fronts of attached vertebrae (at the level of the diaphragm), down and back; the abdominals push the same area back.

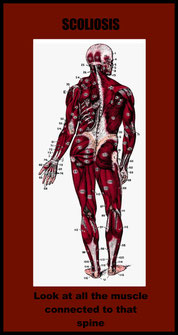

One-sided contraction of the psoas muscles twists the torso and causes a sidebend toward the side of contraction (as if ducking to one side and looking over ones raised shoulder) -- it also

retracts (pulls in) the leg toward the waist from within; abdominal muscles assist the shortening movement by pulling the hip (iliac crest) into the waist (part of being short-waisted). Now, if

this all sounds complicated, well, it is. Fortunately, we don't need to keep all this in mind when doing a self-relief program. In a self-relief program such as this one, you just follow

step-by-step instructions. If you're concerned that you won't get them right, don't worry. You can get coaching. Preview a Guaranteed Self-Relief Muscle/Movement Memory Training Program

Unexpected Other Symptoms Of Psoas Muscle Malfunction Exercises to flatten the belly (e.g., crunches) cause the abdominal muscles to overpower psoas and spinal extensor muscles that are already

too tight. Co-contraction results, in which abdominal organs are sandwiched between tight muscles, front and back, which impairs their functioning (e.g., digestive/eliminative problems)

High abdominal muscle tone from abdominal crunches drags the front of the ribs down and causes a head-forward position. Results: (1) impaired breathing, (2) compressed abdominal contents with

impaired circulation, (3) sluggish lumbar plexus function (4) chronic constipation (from sluggish lumbar plexus function), (5) poor postural alignment, (6) poor support; gravity then drags

posture down, (7) muscular involvement (at the back of the body) to counteract what is, in effect, a movement toward collapse. This muscular effort (a) taxes the body's vital resources, (b)

introduces strain in the involved musculature (e.g., the extensors of the back), and (c) sets the stage for back pain and back injury.

From the foregoing description, it's obvious that "inconvenient" consequences result from abdominal exercises -- as popular as those exercises are for the appearance of fitness. It's better to

simply to balance the interaction of the psoas and abdominal muscles.

The musculature and connective tissue of the legs, which connect the legs with the pelvis and torso, largely determine the pelvic orientation (postural position), and thus the spinal curves. If

the feet are not in the same vertical plane as the hip joints, but are somewhat behind the hip joints(swayback), or more ahead of them (the stooped posture of "old age"), the strain tilts the

pelvis -- and excessive lordosis or kyphosis follows (depending on whether the person has a swayback or a stoop). This postural effect involves the postural reflexes of standing balance, reflexes

that involve the abdominal musculature. If the psoas muscles are tighter on one side than the other (pain on one side), abdominal muscles are tighter on one side than the other, and hip height

asymmetry results, contributing to the appearance of unequal leg length.

Where movement, abdominal organ function, and freedom from back pain are concerned, proper support from the legs is as important as the free, reciprocal interplay of the psoas and abdominal

muscles. Preview a Guaranteed Self-Relief Muscle/Memory Training Program

Signs of Psoas Health When the psoas and the abdominal muscles counterbalance each other, the psoas muscles contract and relax, shorten and lengthen appropriately in movement. The lumbar curve,

rather than increasing, decreases; the back flattens and the abdominal contents move back into the abdominal cavity, where they are supported instead of hanging forward. Dr. Ida P. Rolf described

the role of the psoas in walking: Let us be clear about this: the legs do not originate movement in the walk of a balanced body; the legs support and follow. Movement is initiated in the trunk

and transmitted to the legs through the medium of the psoas. (Rolf, 1977: Rolfing, the Integration of Human Structures, pg. 118). (A TECHNICAL DISCUSSION OF BALANCED WALKING)

What this means is that movement forward starts in the trunk (as a slight swaying forward). That slight swaying forward starts as a shifting of weight onto one foot and a subtle lifting of the

toes and/or front of that foot, which decreases support, so that you slightly sway forward. When you have swayed far enough forward, you spontaneously bring your other leg forward to catch your

forward weight (knee movement forward initiated by the psoas). Your leg comes forward, your foot comes down and supports your weight as it comes forward; then your other leg comes forward. The

movement is: foot, trunk, hip, knee, foot, in a cycle.

A casual interpretation of this description might be that the psoas initiates hip flexion by bringing the thigh forward. It's not quite as simple as that. By its location, the psoas is also a

rotator of the thigh. It passes down and forward from the lumbar spine, over the pubic crest, before its tendon passes posteriorly (back) to its insertion at the lesser trochanter of the thigh.

Shortening of the psoas pulls upon that tendon, which pulls the medial aspect of the thigh forward, inducing rotation, knee outward.

In healthy functioning, two actions regulate that tendency to knee-outward turning: (1) the same side of the pelvis rotates forward by action involving the iliacus muscle, the internal oblique

(which is functionally continuous with the iliacus by its common insertion at the iliac crest) and the external oblique of the other side and (2) the gluteus minimus, which passes backward from

below the iliac crest to the greater trochanter, assists the psoas in bringing the thigh forward, while aligning thigh rotation so the leg (optimally) swings directly in the line of travel (not

commonly seen, but then idiosyncratic muscular tensions and inefficient movement are more common than well-organized movement -- so common that they are taken as "normal"). The glutei minimi are

internal rotators, as well as flexors, of the thigh at the hip joint. They function synergistically with the psoas.

This synergy causes forward movement of the thigh, aided by the forward movement of the same side of the pelvis. The movement functionally originates from the somatic center, through which the

psoas passes on its way to the lumbar spine. Thus, Dr. Rolf's observation of the role of the psoas in initiating walking is explained.

Interestingly, the abdominals aid walking by assisting the pelvic rotational movement described, by means of their attachments along the anterior (front) border of the pelvis. Thus, the interplay

of psoas and abdominals is explained. A final interesting note brings the center (psoas) into relation with the periphery (feet). In healthy, well-integrated walking, the feet assist the psoas

and glutei minimi in bringing the thigh forward. The phenomenon is known as "spring in the step."

Here's the description: When the thigh is farthest back, in walking, the ankle is most dorsi-flexed. That means that the calf muscles and hip flexors are at their fullest stretch and primed by

stretch receptors, in those muscles, to contract. This is what happens in well-integrated walking: assisted by the stretch reflex, the plantar flexors of the feet put spring in the step, which

assists the flexors of the hip joints in bringing the thigh forward. Here's what makes it particularly interesting: when the plantar flexors fail to respond in a lively fashion, ones feet lack

spring and the burden of bringing the thigh forward falls heavily upon the psoas and other hip joint flexors, which become conditioned to maintain a heightened state of tension and readiness to

contract, and there we are: tight psoas and back pain. Note that ineffective dorsi-flexors of the feet (lifters of the fronts of the feet) lead to tripping over ones feet, when walking; to avoid

tripping over ones own feet, the hip flexors must compensate by lifting the knee higher, leading to a similar problem. The answer to this problem, by the way, is not usually to strengthen the

muscles of the shin (dorsiflexors), but to free the muscles of the calf, which are usually too tight. Thus, it appears that the responsibility for problems with the psoas falls (in part, if not

largely) upon the feet. No resolution of psoas problems can be expected without proper functioning of the lower legs and feet.

(TECHNICAL DISCUSSION ENDS) The psoas muscles have gotten a lot of recognition, these days -- often cited as the cause of back pain. If you have both tight psoas muscles and pain around the

pelvic rim or in the hip joint, it's likely you have a twisted sacrum* (S-I joint dysfunction) -- a common condition. In that case, tight psoas muscles are an effect of a twisted sacrum, not the

underlying cause of the pain, and your psoas muscles can't be released without first correcting sacrum position. Movement patterns and muscle tensions maintain sacrum position, so mechanical

adjustments are of limited effectiveness.

To determine whether you have that a twisted sacrum, read and follow the instructions in this entry on S-I joint dysfunction. If the entry seems to be describing you, click on the "regimen" link

at the bottom of that entry; an email window will open; send the email (blank) and you will receive a "quick response" email message with access to the self-relief regimen. * The sacrum is the

central bone of the pelvis, running from the waistline in back to the tailbone.

SUMMARY Because psoas problems are really movement and control problems (dysfunctions of "muscle memory/movement habit" problems), somatic education provides a better solution for the problem of

psoas pain or back pain than strengthening, stretching exercises, massage or manipulation, which cannot improve control and coordination. When one side of the psoas is tight and short, it's the

result of muscle/movement memory. Stretching doesn't change muscle/movement memory. Strengthening doesn't correct the problem. Tight psoas muscles contribute to fatigue, sitting.

Postural changes include a back-arched, big-belly posture tending toward a forward-bending posture, which the extensors of the lumbar spine counter to keep you upright, sometimes leading to back

fatigue. Click for Tight Psoas? Read a description of a clinical somatic education session. See somatics in action. As explained, stretching tight psoas muscles is a misguided effort, as is

tightening the abdominal muscles. To free and coordinate your psoas and the other, central movers and stabilizers of the body, you need to correct your muscle/movement memory.

What You Can Do For Yourself Somatic education exercises directly relieve psoas muscle pain and related conditions, such as iliopsoas bursitis. They change muscle/movement memory pulls, muscle

tone, and coordination over a course of comfortable practice sessions. The result: you feel better put-together and move better, fit for all other forms of exercise and activity. You have access

to somatic education exercises in the self-relief program, Free Your Psoas, for which you may see a preview and do a free two-week test. Two weeks is more than enough to feel results; you will

feel postural and movement changes "in the right direction" within the first three days, and to some degree, within the first hour, of practice. Symptoms of Psoas Dysfunction groin pain iliopsoas

bursitis/tendinitis restriction moving the thigh backward deep pelvic pain, on the tight side deep "bellyache" chronic constipation twisted pelvis If you have deep hip joint pain, a feeling like

a tight wire going down your low back, and/or pain at the waistline on one side, in back, please click here for the write-up and regimen for that condition.

© 2004 Lawrence Gold |

revised Jan 2010 certified practitioner

Hanna Somatic Education®

The Dr. Ida P.

Rolf method of Structural Integration This Psoas

Article was found @ http://www.somatics.com/psoas.htm#FEELS LIKE

Fig 1. Dissected specimens of the iliotibial band on the left leg viewed posteriorly (A) The circumferential nature is demonstrated and the location of ITB. (B) The ITB is a lateral

thickening of the fascia latae rather than a discrete entity.

Fig 1. Dissected specimens of the iliotibial band on the left leg viewed posteriorly (A) The circumferential nature is demonstrated and the location of ITB. (B) The ITB is a lateral

thickening of the fascia latae rather than a discrete entity. Fig 3. Strain measured in the ITB during the three different testing protocols.

Fig 3. Strain measured in the ITB during the three different testing protocols.